This column originally appeared in NOLA.com

Over the course of 10 days in March and April, three historically black churches – Greater Union Baptist Church, St. Mary Missionary Baptist Church and Mount Pleasant Baptist Church – were intentionally set ablaze in St. Landry Parish.

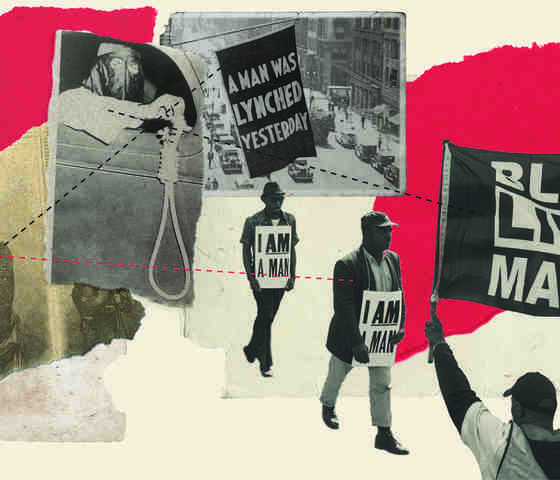

These destructive acts of violence harken back to some of the darkest chapters of the Jim Crow era. They are also a reminder of the rising threat of racial violence and intimidation that black communities face to this day.

Holden Matthews, the white, 21-year-old son of a sheriff’s deputy, has been charged with arson and hate crimes. And the evidence is overwhelming that these were acts of domestic terrorism intended to terrorize and intimidate the black community.

There are nearly two dozen churches in St. Landry Parish, which is majority white. The churches Holden chose to destroy all had predominantly black congregations.

In his public comments, Gov. John Bel Edwards took pains to frame these violent acts as outliers and not representative of the state as a whole. But history tells us that these incidents are all too representative of the lived experience of generations of black Americans across the South.

The Equal Justice Initiative has documented 4,084 racial terror lynchings in 12 Southern states between the end of Reconstruction in 1877 and 1950, including 549 in Louisiana. In 1872, as many as 150 black Americans were massacred in Colfax for protesting fraudulent election results orchestrated by former Confederates in the Democratic Party.

These terror lynchings and massacres were not random. They had a sinister and specific purpose: to enforce racial subordination and uphold white supremacy by subjecting black communities to profound trauma, torture and humiliation.

Black churches, as centers of hope and resilience for African Americans, have been habitual targets of racial violence and terrorism long after the Jim Crow era. In 1963, the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., was bombed – killing four girls. Between 1995 and 1996, 145 black churches burned, including nearly a dozen in Louisiana.

Today, terrorist acts from Pittsburgh to New Zealand indicate that violence by white supremacists is on the rise and becoming a global threat around the world.

That’s why it’s on all of us to speak out against hate and intolerance and to stand in solidarity with the communities affected by these tragedies.

But we can’t stop there.

We also have a shared responsibility to take an honest, unflinching look at our history and recognize that these attacks are not isolated incidents. They are part of a pattern of racial violence and terrorism designed to subjugate black Americans and uphold white supremacy.

Four hundred years after the first slaves were forcibly and violently brought to these shores, too many Americans are still reluctant to acknowledge the legacy of white supremacy that is hard-wired into our institutions – and even written into our national anthem.

Instead, Confederate generals continue to be lionized in our public spaces. And even in Colfax – the site of that 1872 deadly massacre – a plaque still stands that celebrates the event as “the end of carpetbag misrule in the South.”

Together, these symbols perpetuate the living legacy of white supremacy – papering over its brutality and recasting it as a noble and patriotic cause.

This white-washing of American history – which omits these critical accounts of violence and terror – deprives all Americans, white and black, of a true appreciation of our past and hinders our understanding of the racial prejudice that pervades our society to this day.

This must change.

As Bryan Stevenson, the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative and a recipient of the ACLU’s National Medal of Liberty, reminds us: Reckoning with our dark past is vital for our nation to heal and move forward. There can be no reconciliation without truth.

Confronting the enduring legacy of white supremacy in the present starts by recognizing the ugly truth of our past.

Date

Wednesday, April 24, 2019 - 2:45pmFeatured image